The New Adits festival in Klagenfurt – Austria

The New Adits festival in Klagenfurt – Austria

written by Andrew Choate

A nervous tingle, like a bared fang from a mellow wolf, hung in the air throughout the four days (September 22-25, 2021) of the New Adits festival in Klagenfurt, Austria. Sometimes due to thrills reverberating from a performance, at other times due to awkwardnesses arising from remembering how to share culture in public: anticipations, applause, flirting, drinking, and, most importantly, relearning the quieting of the self required in order to experience performance. No pausing, no looking away from the screen, no distance from the event. What a relief and a celebration: to be back in total lack of control.

Installation by Andreas Trobollowitsch. Photo: Ola Queen

That lack of control, and the willingness to not only submit to it, but also engage with it, and to go one step further: to design a careful engagement with the act of submitting to loss of control – this act was at the heart of the work by the festival’s first artist, Andreas Trobollowitsch. He made an installation with four acoustic guitars hanging vertically upright on a wall, and set up oscillating motors with hair from violin bows to sway across the strings; each guitar with only three strings, each tuned to a different chord. Because of the multiple physical variabilities––how long the strings stay tuned; the changing distance of the motors/hairs to the strings; the waves of a/synchronization between the moments of hair striking the strings; the shape of the room; the shape of the bodies in the room; etc.––the installation changed radically, mesmerizingly subtly radically. Not only from minute to minute, but from day to day as well. Because the installation not only inaugurated this edition of the festival, but it was turned on between sets each night as well, functioning like the opposite of an alarm: when it was on, you were “between things”; when off, something was happening.

The variety of sounds, rhythms, and reverberating harmonic waves also changed significantly depending on where you stood in the room. The combination of the false arco from the guitars with the vibration of the motors put a wild whirr of beats in the room, like surfing on reverb. With so many opportunities to hear the installation, I discovered the delicacy of physicality Trobollowitsch engaged. The fans and guitars had minds of their own: sometimes the fan jostled back a micrometer, causing the sound to completely disappear, or a guitar leaned one squeak closer, unpleasantly magnifying the action. He monitored the installation, but not too too closely, only adjusting its twitches and leanings in acute detail when necessary, preferring to allow the installation to develop its own breath.

Wolfgang Mitterer. Photo: Ola Queen

Wolfgang Mitterer. Photo: Ola Queen

Native to Klagenfurt, the composer/improviser/keyboardist/electronicist Wolfgang Mitterer performed his Grand Jeu 2 on the organ at the Klagenfurt Cathedral a few blocks away. Augmented by electronics, the piece is a “half-composed journey from György Ligeti’s Volumina (1962) to the 21st Century.” I loved the single notes in the upper register that opened the performance, but the transition to dense, busy chords came so quickly that they felt unearned and unwarranted. In the dramatically gilded and carefully appointed atmosphere of this church, I needed to be coaxed into full aural attention, away from the lavishness and detail of the surroundings, rather than ambushed. Unfortunately, the music, for the most part, had a hard time competing with the physicality of the space.

Digital electronics are already at a disadvantage when placed next to the mechanical and aural magnificence of a robust organ, so Mitterer’s additions of thin flute-y shards felt tonally inappropriate to my ears. Cascades of artificially buzzing beehives paled next to the energy of giant pipes blaring and blasting, though I did appreciate the way he moved the sound around the room with his electronics, fabricating a Doppler effect from left to right or back to front, like an airplane landing on your forehead and immediately taking off to the heavens. Occasional moments of carnivalesque playfulness were enjoyable but misplaced, not enough of a humorous tone having been established to ground the sounds in any way beyond kaleidoscopic kitsch. Though I found the piece too scattered and uncommitted, without even a collage’s flow, the final hallelujah-like major chord resonated with such direct boldness and obviousness as to be an absolutely proper finale.

The rest of the festival took place back at the beautiful Villa FOR FOREST, a former mansion that now offers outstanding arts programming. Mia Zabelka wasn’t feeling well and canceled her performance at the last minute, so the organizers improvised and added a playback of tape music by Isabelle Forciniti. Tape music is already an important feature of this festival, as work by six other composers was on the program, and I appreciated it immensely each night since I, like most people, don’t have a 4, 6, or 8-channel speaker setup at home, and thus don’t get a chance to hear this music the way it was made to be heard.

Forciniti’s piece was like a collage of the greatest moments from INA-GRM’s 1970s catalogue: thick and wet electronic timbres zooming in and out of focus. She wasn’t afraid of incorporating dance beats either, however fractalized and refracted. Sounds squirted back and forth from one of four speakers on one side of the room––set up in two layers of two––and two more on the other side of the audience. Tiny threads of pitch unfurled, with each thread adding a ripple of interference. I love the texture of this kind of electronic work and lapped it up.

Peter Kutin and Dario San Filippo. Photo: Ola Queen

Peter Kutin and Dario San Filippo. Photo: Ola Queen

The final set on this first evening was a duo of Peter Kutin and Dario San Filippo on various electronics. The visual element of Kutin’s performance was equally as central as the music, even distractingly centerstage, to the point where it overwhelmed the rest of my attention. He used what looked like a dual-pronged laser lightstick that rotated at various speeds to produce images as complex as patterns or as simple as a spinning line. It strobed and went in an out of sync with the other lights in the room. It sounds simple, but the flashing on and off in odd patterns was combined with slashes of high-decibel onslaught for a rather off-putting result. His website says that his performances offer “a physical and psychological impact that throws you as much off balance as it will embrace you.” I simply found it unpleasant. Not because it was so intense––it was too haphazard to generate intensity––but because the intensity it desperately desired to display was so basic: loud and bright.

After reading about what Kutin is trying to do, it reminded me of an audiovisual performance by Cellule d’Intervention Metamkine (Cristophe Auger, Xavier Quérel and Jérôme Noetinger) I saw in the mid-90s at Chicago Filmmakers. Three projectors were on the ground. Auger and Quérel went back and forth between them, manipulating the films and the film itself as it ran through the projector with ink, scissors, abrasions, fire, etc. Noetinger made music to accompany. The reason I’m thinking about it is because their performance did what Kutin wants to do: create “an uncanny dialogue between the trinity of ‚object-sound-light‘ and the audience.” The physicality of mechanical machines, actual objects and human activity added up to something that Kutin’s use of digital light and sound did not.

I couldn’t tell what San Filippoi was contributing to the audiovisual mix, but since the brunt of the performance was overbearingly focussed on the visuals, I’m not sure what kind of audio could have competed with the barrage. The set in six words: lots of light, some loud sounds.

Matthias Erian. Photo: Ola Queen

Matthias Erian. Photo: Ola Queen

Achtung Vavoom

Krebs used other sped-up and distorted text-speech files, accompanied with ringing here and there. I’d like to hear more of her work in this area as I’m only familiar with her guitar and mixing board activity, and the way she adjusted these language files gave me the sense that an altercation between the mediums was just under the surface but not yet expressed.

Martina Clausen’s two pieces were deftly mixed live by Lisa Rožmann from two channels into six speakers. The angelic voices in the first provided thick contrast to the slow clicking of wind-up toys in the second. Crunched footsteps, bells and cabinets added a concrète vibe that narrowly avoided narrative explicability.

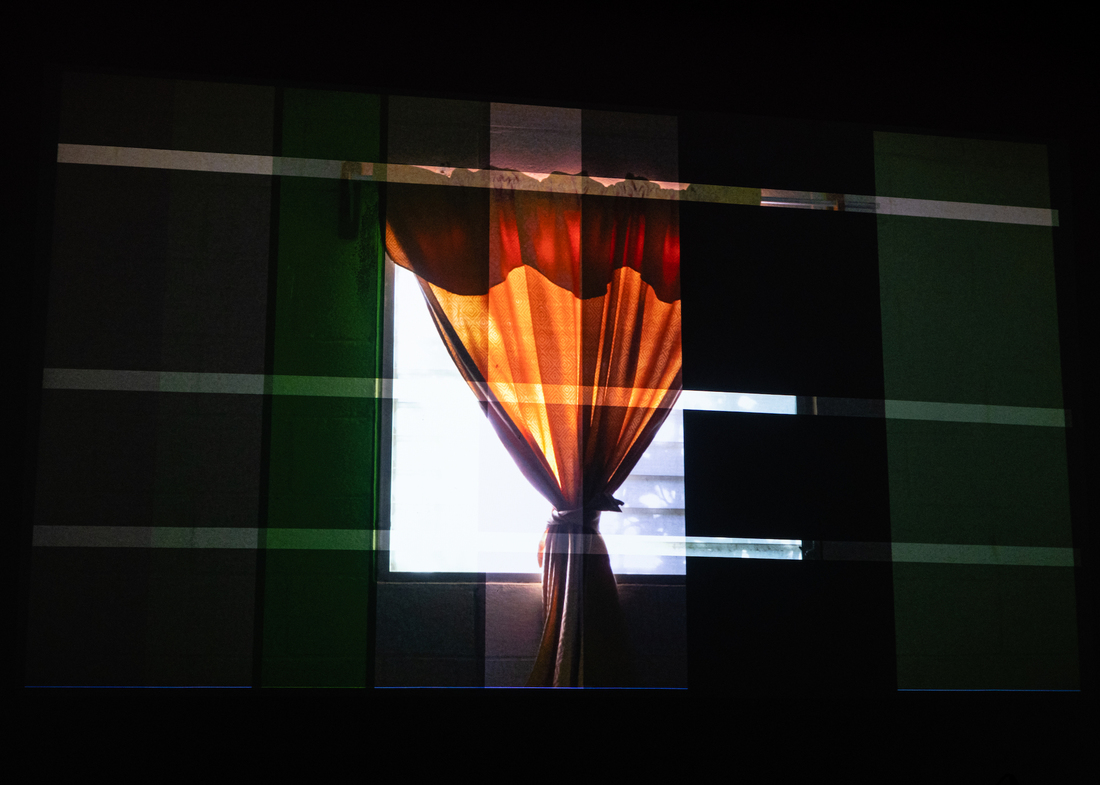

Matthias Erian’s solo set focussed just as much on the visual element as Kutin and San Fillipoi’s from the night before, but instead of attempting to overpower the audience, he built the performance like a poem: inviting us in, teaching us his vocabulary of light and sound, testing the limits of our comprehension of it vs. his use of it, developing a denouement and then letting it, and us, go.

Light in sunset colors (thin pinks, mild blues) flashed behind and in front of us; soft poofs of sound flashed behind and in front of us. Airy sounds, with plenty of oxygen within them, appeared and dissipated. Silent, brief flashes of soft light appearing from within small parentheses of a silent, dark field of attention almost brought a tear to my eye, so carefully and perceptively placed they were. Such nimble moves made the rare positive case for the use of visuality as a compositional touchstone, since it usually feels like something added out of desperation when the music isn’t enough on its own.

To the contrary, visual elements in the foreground allowed Erian to develop multiple rhythms at one time: from one close to breath to another steadier, like a pulse. Even the asynchronicity of popcorn rhythm––starting slow, getting fast, then stopping in a scatter––was employed to significant effect. As he added depth upon depth during this performance, his source of sounds and imagery expanded as well. It started with abstractions, but proceeded to include blips of light in combination with images of objects (windows, curtains, etc.). And the same with the sounds: field recordings of a barn door opening (or was it a dry bow being rubbed across a string instrument?) alternated with hissy electronic thops and thorps. A gorgeous, sure-handed set that satisfied aesthetic and emotional cravings I didn’t even know I had.

A solo set by British pianist Kit Downes followed; it felt like cinematic luxury for the voyeur of experience. Low-end throbbing with alternating pedal pumps. Boat on a dark sea, little bit of moonlight on the waves to offer suggestive glimmers. But no knife blades wielded: no rugged drama, just breezy, easy bobbing on the waves. I wasn’t familiar with his work, so I looked him up just now and he’s quite acclaimed by The Guardian and Downbeat; considering their expertise on what I consider middle-of-the-road culture, it makes sense. Nothing to grip here, simple to slide by and pass for wild: a boneless, skinless chicken breast of music.

The evening concluded with a performance by the one-woman show Electric Indigo. Somehow she balanced ambient noise with techno-pop and came out the other side having gifted the audience with a new swing. Using four channels, she incorporated everything from groovy drum-circle percussion and metal trashcan-lid clatters to Gregorian humming and alien spaceship zurbung xrlings. Her digital sounds didn’t sound tiny or tinny; they possessed dense layers of woofer and fuzz. I pictured warm hugs at nymph picnics around a gold-speckled marsh.

Once the weird sounds were established, she got to work building beats. Clearly comfortable in this zone, she also began dancing to the regular rhythms, then adding more twisted beats to percolate within those already established. Cool stylings, engaging combinations.

Liebster Come Hither

Lisa Rožmann took the mixing reins for Liz Allbee’s “Slow Dance” and it felt more like a piece for organ than tape. I fell into it completely and submitted to being perfectly led by an expert dancer through the gentlest libidinal surge.

Video projections added to music have two routes to failure: either they are so innocuous to the performance as to become an irrelevant distraction, or they are so dominant that their force saps the strength away from the music. Anton Iakhontov’s visual contribution to the improvised music of Ingrid Schmoliner on piano and Jakob Schneidewind on electric bass/sampler completely avoided both of those tendencies, instead becoming a vital force propelling the music from outside. And yet, because his projections were instantly in tune with the sounds––rather astonishing for a first-time, blind-date performance––, they became so deeply entwined with the sonics as to be inseparable from them, allowing the music to nourish and nurture his own developments in black and white light happening on the wall above them all.

I can’t stress enough how surprised I was to experience such an organic envelopment and unfolding of the two mediums. Beyond synaesthesia, this was two mediums working together to create a hybrid third.

For folks unfamiliar with the radical variety of music that gets made under the umbrella of Improvised Music, this set would spark a lot of questions. Because the sequence of music and all the interactions were clearly improvised, but decisions were also clearly made ahead of time about how the improvisation would be constructed. For example, Schmoliner began with a strictly defined pattern of key strikes on the prepared piano––six or seven notes circling each other rapidly, with chaotic regularity, like the vortex at the edge of a whirlpool––while Iakhontov also had a sequence ready to go at the start––five vertical strips, each displaying a variation of a simple geometrical alignment––and Schneidewind bridged the two layers with deeply resonant echoings of ambient bass thumpery.

I was completely engrossed. Iakhontov used refrains of shapes, patterns and zooms in such a musical sense that the sounds of the musicians nonchalantly implied sculptural depth and precision. The momentum of rhythms and patterns intertwining in deeper and deeper complexities as the set progressed caused an increase in tension as well, like pushing closer and closer to the abyss. But they all navigated smoothly, effectively engaging restraint and negative space to avoid any sense of inevitability or unidirectionality. Enriching, enriched, enrichment.

What really impressed me was her vocal breath play: she used the moments between lines to play with her breath, the way Sammy Davis Jr. and David Lee Roth expertly added exhales and improvised phonemes to emotionally accentuate lyrics. While each of these three performers work/ed in different genres, the foundation of their music is stage presence, and Koi belongs with them in that regard as well. Her intimate lyrics are a combination of risqué innuendo, awkward TMI, supercharged satire and emo subterfuge. So fucking fun. Also, sometimes there is no innuendo: it’s just straightforward, dirty fun. Even when what she’s singing about is embarrassing or lewd, her gorgeously enunciated vocalizations wickedly put you under her spell. I smiled a lot listening to her. A skillful demonstration of tongue-in-cheek-in-wait!!-who’s-tongue-is-that?? songwriting plus pitch-perfect musicality. Infectious, graceful, pleasurable.

The singer/songwriter Sir Tralala opened his set with a lot of back-and-forth wordplay with the kids in the audience. Since the wordplay was in German, and my German is kaput, genau, the content was lost on me. What wasn’t lost, however, was the fact that the kids and most of the audience were having a delightful time. Or a delightfully frustrating time, as Tralala would describe a song––as an ode to getting shot for example, pause, ‘shot’ meaning vaccinated, anschlock––and then start to play it, and then interrupt himself within fifteen seconds and begin another dialogue with the kids, getting the kids to groan and the adults to laugh. This went on for a while, and I was genuinely entertained. Many uproarious guffaws exploded around me.

It took a pretty long time, but he settled into his set and the wordplay didn’t get any less layered: krampus, cactus, krampusé, krampagne, cactaine, krampus on campus, etc. I listened and enjoyed the sounds of the words, even if I was in an igloo of spinach mixing up street and strudel, sugar went down a dark hole, I’ve never heard of it, it’s okay, you’re okay, it’s not angst, it’s neuronst, I got tired, the venue Villa FOR FOREST––where all these events took place–– exists because Klaus Littmann built a forest inside the nearby Wörthersee soccer stadium.

You Play Badminton, I Play Batman

Because the duo writes and learns only one composition per year, it was also a thrill to hear a new piece by the duo. They called this one a ‘noise piece’, and it did have elements that had been lacking in previous compositions by the duo, notably non-breath-exclusive clarinet sounds. But one thing should be made clear: they play gigantically minimal music. Not in terms of length or audacity like some Feldman pieces, or endurance-listening like that required by early Pisaro, but in terms of intensity: the dynamic is between tight focus and tighter focus. Even within the intimacy of performing in the tape music room, the set felt humongous, like living within a parabola, and being fine with it.

Their music isn’t always quiet, but when it was, you could hear the breath of the other people in the room, and it was as peaceful as a pond. If you were a frog. And hungry. And lusty.

Speaking of tape music, Lisa Rožmann was at the mixing console again, first projecting Isabella Forciniti’s “Paranoid”, the same tape piece we heard on Thursday. Electroacoustic video game pop. If I trace two small bushes, each less than a meter high, and overlap the tracings, then convert the drawing into a player piano roll, and feed it to a Korg or Moog product, would I get something similar? No. I’d need more contained edges and a sense of plateau-acceptance.

Marta Zapparoli’s tape piece had the wind sounds and the electronic hums and the jarring appearance of discontinuous elements: in short, the drama of health, assurance and captivity, plus an overture toward the minor crimes necessary to achieve a willing glance.

Bernhard Rasinger’s live set was another combination of projection and sound, this time one person in control of both. His setup alone was something to behold: so many tubes and cords and flashing buttons and switches. While each night had an audiovisual performance, the variety of methodologies employed was quite wide. Rasinger utilized a laser partially tuned like it was an oscilloscope. Because he was overseeing both mediums, his sonic decisions were more obviously in significant alignment with his visuals, sometimes with less energetic effect compared to Iakhontov’s the night before, and sometimes with more liminal tension harnessed as he could overtly tantalize the edges of the sounds and sights. Rasinger’s performance grandly harnessed the mighty awe of Robin Fox’s 2007 Backscatter DVD while implying hints toward the Color-QuadraScan vector display technology first introduced in the 1980 Atari arcade game Tempest. It’s clear that the use of lasers in audio-visual performance is only going to increase; I’m rooting for the spectrum that targets the botanical/mineral mindset.

The festival closed with a set by Dog Dimension (Josefine Lukschy – bass, vocals; Alexander Meurer – guitar; Immo Philipp Hofmann – drums). A vigorous flurry of beach-punk, glam-funk, wine-fuck, dog-rock. We all stood up and danced and shook and cavorted to lyrics like “I’m drowning in the noise right where I want to be.” Fu Manchu + Joan Jett + The Dead Milkmen with a female vocalist and bassist at the center of the maelstrom. They’ve got a song called “Doggernaut” so you know I became an adherent there and then.

New Adits was started eleven years ago, at a time when the right wing was in power in Austria. As one of the founding organizers, Raimund Spoeck, told me “it was a common decision [for Matthias Erian, Ingrid Schmoliner, Martin Schönlieb and himself] that in the worst time for such cultural activities, we should do it.” And as a response to that governing power, they also decided that it should happen in Carinthia, not in Vienna or Berlin, where some of these exiled Carinthians now resided. So the political aspect has never been far from the surface. The act of placing the performances that happen at the festival next to each other––improvised music alongside tape music alongside musical theatre alongside audio-visual electro-acoustics––raises as many eyebrows from self-proclaimed avant-garde circles as it does from professional cultural critics. Thankfully for me––and hopefully for you––, it’s also possible to listen without camping under a single shelter.